Network

Bringing Ouroboros to the people

Introduction

This document highlights the requirements we wish to apply to a decentralised network applied to cardano blockchain. Then we will discuss the possible solutions we can provide in a timely manner and the tradeoff we will need to make.

Design decisions guidelines

This is a main of general guidelines for the design decision in this document, and to judge the merit of solutions:

- Efficiency: the communication between the nodes needs to be succinct. to the point, avoiding unnecessary redundancies. The protocol needs to stabilise quickly to a well distributed network, guaranteeing a fast propagation of the important events;

- Security: limit the ability for other nodes to trigger behavior that would prevent a peer from working (e.g. unbounded resources usage)

- Simplicity: we need to easily implement the protocol for any platforms or environment that will matter for our users.

Node-to-Node communication

This section describes the communication between 2 different peers on the network. It involves synchronous queries with the context of the local state and remote state.

General Functionality

This is a general high level list of what information will need to be exchanged:

- Bootstrap local state from nothing

- Update local state from an arbitrary point

- Answer Synchronous queries: RPC style

- Asynchronous messages for state propagation (transactions, blocks, ..)

- P2P messages (See P2P Communication)

Design

User Stories

- Alice wants to synchronise its local state from Bob from Alice's Tip:

- Alice downloads Block Headers from Bob (starting from Alice's Tip);

- Bob does not know this Tip:

- Error: unknown block

- Alice starts again with a previous Tip;

- Bob does know this state:

- Bob streams back the block headers

- Bob does not know this Tip:

- Alice downloads block

- Since Alice knows the list of Block Headers and the number of blocks to download, Alice can download from multiple peers, requiring to get block stream from different Hash in this list of Block;

- State: tip_hash, storage

- Pseudocode (executed by Alice):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { sync(): bob.get_headers(alice.tip) }

- Alice downloads Block Headers from Bob (starting from Alice's Tip);

- Alice wants to propagate a transaction to Bob

- Alice send the transaction hash to Bob

- Bob replies whether it want to hear more

- Alice send the transaction to Bob if Bob agrees

- Alice wants to submit a Block to Bob

- Alice sends the Header to Bob;

- Bob replies whether it want to hear more

- Alice sends the Block to Bob if Bob agrees

- Alice want to exchange peers with Bob

High Level Messages

We model everything so that we don't need any network state machine. Everything is stateless for

Handshake: () -> (Version, Hash)- This should be the first request performed by the client after connecting. The server responds with the protocol version and the hash of the genesis block.

- The handshake is used to establish that the remote node has a compatible protocol implementation and serves the right block chain.

Tip: () -> Header:- Return the header of the latest block known by the peer (also known as at the tip of the blockchain).

- DD? : Block vs hash: block is large but contain extra useful metadata (slotid, prevhash), whereas hash is small.

GetHeaders: ([Hash]) -> [Header]:- Fetch the headers (cryptographically verifiable metadata summaries) of the blocks identified by hashes.

GetBlocks: ([Hash]) -> [Block]:- Like GetHeaders, but returns full blocks.

PullBlocksToTip: ([Hash]) -> Stream<Block>:- Retrieve a stream of blocks descending from one of the given hashes, up to the remote's current tip.

- This is an easy way to pull blockchain state from a single peer,

for clients that don't have a need to fiddle with batched

GetBlocksrequests and traffic distribution among multiple peers.

BlockSubscription: (Stream<Header>) -> Stream<BlockEvent>- Establish a bidirectional subscription to send and receive announcements of new blocks and (in the client role) receive solicitations to upload blocks or push the chain of headers.

- The stream item is a tagged enumeration:

BlockEvent: Announce(Header)|Solicit([Hash])|Missing([Hash], Hash)Announcepropagates header information of a newly minted block.Solicitrequests the client to upload blocks identified by the given hashes using theUploadBlocksrequest.Missingrequests the client to stream the chain of block headers using the given range parameters. The meaning of the parameters is the same as in thePullHeadersrequest.

- The client does not need to stream solicitations upwards, as it can

request blocks directly with

GetBlocksorPullHeaders. - The announcements send in either direction are used for both announcing new blocks when minted by this node in the leadership role, and propagating blocks received from other nodes on the p2p network.

PullHeaders: ([Hash], Hash) -> Stream<Header>- Retrieve a stream of headers for blocks descending from one of the hashes given in the first parameter, up to the hash given in the second parameter. The starting point that is latest in the chain is selected.

- The client sends this request after receiving an announcement of a new

block via the

BlockSubscriptionstream, when the parent of the new block is not present in its local storage. The proposed starting points are selected from locally known blocks with exponentially receding depth.

PushHeaders: (Stream<Header>)- Streams the chain of headers in response to a

Missingevent received via theBlockSubscriptionstream.

- Streams the chain of headers in response to a

UploadBlocks: (Stream<Block>)- Uploads blocks in response to a

Solicitevent received via theBlockSubscriptionstream.

- Uploads blocks in response to a

ContentSubscription: (Stream<Fragment>) -> Stream<Fragment>- Establish a bidirectional subscription to send and receive new content for the block under construction.

- Used for submission of new fragments submitted to the node by application clients, and for relaying of fragment gossip on the network.

- P2P Messages: see P2P messages section.

The protobuf files describing these methods are available in the

proto directory of chain-network crate in the

chain-libs project repository.

Pseudocode chain sync algorithm

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct State { ChainState chain_state, HashMap<Hash, Block> blocks } struct ChainState { Hash tip, HashSet<Hash> ancestors, Utxos ..., ... } impl ChainState { Fn is_ancestor(hash) -> bool { self.ancestors.exists(hash) } } // Fetch ‘dest_tip’ from `server’ and make it our tip, if it’s better. sync(state, server, dest_tip, dest_tip_length) { if is_ancestor(dest_tip, state.chain_state.tip) { return; // nothing to do } // find a common ancestor of `dest_tip` and our tip. // FIXME: do binary search to find exact most recent ancestor n = 0; loop { hashes = server.get_chain_hashes(dest_tip, 2^n, 1); if hashes == [] { ancestor = genesis; break; } ancestor = hashes[0]; if state.chain_state.has_ancestor(ancestor): { break } n++; } // fetch blocks from ancestor to dest_tip, in batches of 1000 // blocks, forwards // FIXME: integer arithmetic is probably off a bit here, but you get the idea. nr_blocks_to_fetch = 2^n; batch_size = 1000; batches = nr_blocks_to_fetch / batch_size; new_chain_state = reconstruct_chain_state_at(ancestor); for (i = batches; i > 0; i--) { // validate the headers ahead of downloading blocks to validate // cryptographically invalid blocks. It is interesting to do that // ahead of time because of the small size of a BlockHeader new_hashes = server.get_chain_hashes(dest_tip, (i - 1) * batch_size, batch_size); new_headers = server.get_headers(new_hashes); if new_headers are invalid { stop; } new_blocks = server.get_blocks(new_hashes).reverse(); for block in new_blocks { new_chain_state.validate_block(block)?; write_block_to_storage(block); } } if new_chain_state.chain_quality() > state.chain_state.chain_quality() { state.chain_state = new_chain_state } } }

Choice of wire Technology

We don't rely on any specific wire protocol, and only require that the wire protocol allow the transfer of the high level messages in a bidirectional way.

We chose to use GRPC/Protobuf as initial technology choice:

- Efficiency: Using Protobuf, HTTP2, binary protocol

- Bidirectional: through HTTP2, allowing stream of data. data push on a single established connection.

- Potential Authentication: Security / Stream atomicity towards malicious MITM

- Simplicity: Many languages supported (code generation, wide support)

- Language/Architecture Independent: works on everything

- Protobuf file acts as documentation and are relatively easy to version

Connections and bidirectional subscription channels can be left open (especially for clients behind NAT), although we can cycle connections with a simple RCU-like system.

Node-to-Client communication

Client are different from the node, in the sense that they may not be reachable by other peers directly.

However we might consider non reachable clients to keep an open connections to a node to received events. TBD

ReceiveNext : () -> Event

Another solution would be use use libp2p which also implements NAT Traversals and already has solutions for this.

Peer-to-Peer network

This section describes the construction of the network topology between nodes participating in the protocol. It will describes the requirements necessary to propagate the most efficiently the Communication Messages to the nodes of the topology.

Definitions

- Communication Messages: the message that are necessary to be sent through the network (node-to-node and node-to-client) as defined above;

- Topology: defines how the peers are linked to each other;

- Node or Peer: an instance running the protocol;

- Link: a connection between 2 peers in the topology;

Functionalities

- A node can join the network at any moment;

- A node can leave the network at any moment;

- Node will discover new nodes to connect to via gossiping: nodes will exchange information regarding other nodes;

- Nodes will relay information to their linked nodes (neighbors);

- A node can challenge another node utilising the VRF in order to authentify the remote node is a specific stake owner/gatherer.

Messages

- RingGossip: NodeProfileDetails * RING_GOSSIP_MAX_SIZE;

- VicinityGossip: NodeProfileDetails * VICINITY_GOSSIP_MAX_SIZE;

- CyclonGossip: NodeProfileDetails * CYCLON_GOSSIP_MAX_SIZE;

A node profile contains:

- Node’s id;

- Node’s IP Address;

- Node’s topics (set of what the node is known to be interested into);

- Node’s connected IDs

Design

The requirements to join and leave the network at any moment, to discover and change the links and to relay messages are all handled by PolderCast. Implementing PolderCast provides a good support to handle churn, fast relaying and quick stabilisation of the network. The paper proposes 3 modules: Rings, Vicinity and Cyclon.

Our addition: The preferred nodes

We propose to extend the number of modules with a 4th one. This module is static and entirely defined in the config file.

This 4th module will provide the following features:

- Connect to specific dedicated nodes that we know we can trust (we may use a

VRF challenge to validate they are known stakeholder -- they participated to

numerous block creations);

- This will add a static, known inter-node communications. Allowing users to build a one to one trusted topology;

- A direct application for this will be to build an inter-stake-pool communication layer;

- Static / configured list of trusted parties (automatically whitelisted for quarantine)

- Metrics measurement related to stability TBD

Reports and Quarantine

In order to facilitate the handling of unreachable nodes or of misbehaving ones we have a system of reports that handles the state of known peers.

Following such reports, at the moment based only on connectivity status, peers may move into quarantine or other less restrictive impairements.

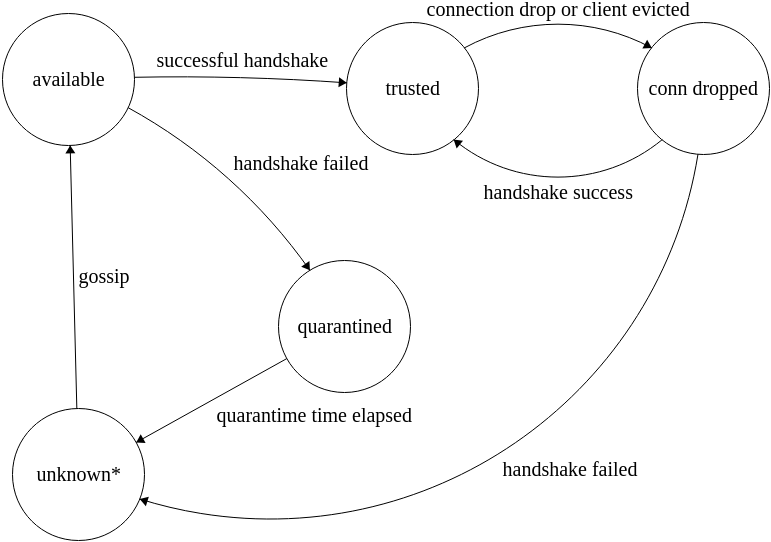

In the current system, a peer can be in any of these 4 states:

-

Available: the peer is known to the current node and can be picked up by poldercast layers for gossip and propagation of messages. This is the state in which new peers joining the topology via gossip end up.

-

Trusted: the last handshake between the peer and this node was successfull. For these kind of nodes we are a little more forgiving with reports and failures.

-

Quarantined: the peer has (possibly several) failed handshake attempts. We will not attempt to contact it again for some time even if we receive new gossip.

-

Unknown: the peer is not known to the current node.

Actually, due to limitations of the poldercast library, this may mean that there are some traces of the peer in the profiles maintained by the current node but it cannot be picked up by poldercast layers for gossip or propagation. For all purposes but last resort connection attempts (see next paragraph), these two cases are essentially the same.

Since a diagram is often easier to understand than a bunch of sentences, these are the transitions between states in the current implementation, with details about avoiding network partition removed (see next paragraph).

Avoid network partitions

An important property of the p2p network is resilience to outages. We must avoid creating partitions in the network as much as possible.

For this reason, we send a manual (i.e. not part of poldercast protocol) optimistic gossip message to all nodes that were reported after the report expired. If this message fails to be delivered, no further action will be taken agains that peer to avoid cycling it back and forth from quarantine indefinitely. If instead the message is delivered correctly, we successfully prevented a possible partition :).

Another measure in place is a sort of a last resort attempt: if the node did not receive any incoming gossip for the last X minutes (tweakable in the config file), we try to contact again any node that is not quarantined and for which we have any trace left in the system (this is where nodes that were artificially forgotten by the system come into play).

Part to look into:

Privacy. Possibly Dandelion tech

Adversarial models considered

Adversarial forks

We consider an adversary whose goal is to isolate from the network nodes with stake. The impact of such successful attack would prevent block creation. Such adversarial node would propose a block that may look like a fork of the blockchain. Ouroboros Genesis allows fork up to an undetermined number of blocks in the past. The targeted would then have to do a large amount of block synchronisation and validation.

- If the fork pretend to be in an epoch known to us, we can perform some cryptographic verifications (check the VRF);

- If the fork pretends to be in an epoch long past, we may perform a small, controlled verification of up to N blocks from the forking point to verify the validity of these blocks;

- Once the validity verified, we can then verify the locality aliveness of the fork and apply the consensus algorithm to decide if such a fork is worth considering.

- However, suck attack can be repeated ad nauseam by any adversarial that

happened to have been elected once by the protocol to create blocks. Once

elected by its stake, the node may turn adversarial, creates as many invalid

blocks, and propose them to the attacked node indefinitely. How do we keep

track of the rejected blocks ? How do we keep track of the blacklisted

stakeholder key or pool that are known to have propose too many invalid block

or attempted this attack ?

- Rejected block have a given block hash that is unlikely to collide with valid blocks, a node can keep a bloomfilter of hashes of known rejected block hash; or of known rejected VRF key;

- The limitation of maintaining a bloom filter is that we may need to keep an ever growing bloom filter. However, it is reasonable to assume that the consensus protocol will organise itself in a collection of stakepools that have the resources (and the incentive) to keep suck bloom filter.

Flooding attack

We consider an adversary whose goal is to disrupt or interrupt the p2p message propagation. The event propagation mechanism of the pub/sub part of the p2p network can be leverage to continuously send invalid or non desired transactions to the network. For example, in a blockchain network protocol the transactions are aimed to be sent quickly between nodes of the topology so they may be quickly added to the ledger.

- While it is true that one can create a random amount of valid transactions,

it is also possible perform a certain amount of validation and policies to

prevent the transaction message forwarding from flooding the network:

- The protocol already requires the nodes to validate the signatures and that the inputs are unspent;

- We can add a policy not to accept transaction that may imply a double spend, i.e. in our pool of pending transaction, we can check that there is no duplicate inputs.

- The p2p gossiping protocols is an active action where a node decides to contact another node to exchange gossip with. It is not possible to flood the network with the gossiping messages as they do not require instant propagation of the gossips.

Anonymity Against distributed adversaries

We consider an adversary whose goal is to deanonymize users by linking their transactions to their IP addresses. This model is analysed in Dandelion. PolderCast already allows us to provide some reasonable guarantees against this adversary model.

- Node do not share their links, they share a limited number of gossips based on what a node believe the recipient node might be interested in;

- While some links can be guessed (those of the Rings module for example), some are too arbitrary (Vicinity or Cyclon) to determined the original sender of a transaction;

Man in the middle

We consider an adversary that could intercept the communication between two nodes. Such adversary could:

- Escalate acquired knowledge to break the node privacy (e.g. user's public keys);

- Disrupt the communication between the two nodes;

Potentially we might use SSL/TLS with dynamic certificate generation. A node would introduce itself to the network with its certificate. The certificate is then associated to this node and would be propagated via gossiping to the network.

In relation to Ouroboros Genesis

Each participants in the protocol need:

- Key Evolving signature (KES) secret key

- Verifiable Random Function (VRF) secret key

Apart from the common block deserialization and hashing verification, each block requires:

- 2 VRF verification

- 1 KES verification.

Considering the perfect network, it allow to calculate how many sequential hops, a block can hope to reach at a maximum bound.